Is honor a strong part of Filipino tradition?

Unquestionably.

Honor is so strong an influence on the average Filipino that we have gotten to be really prickly about it. “Amor proprio,” a commonly used stand-in for the word “honor” actually refers to self-respect, carrying the overtones of pride and self-worth. Not perhaps the most flattering manifestation of how we define the concept of honor, but it does reflect how important the idea of being seen as righteous is to us.

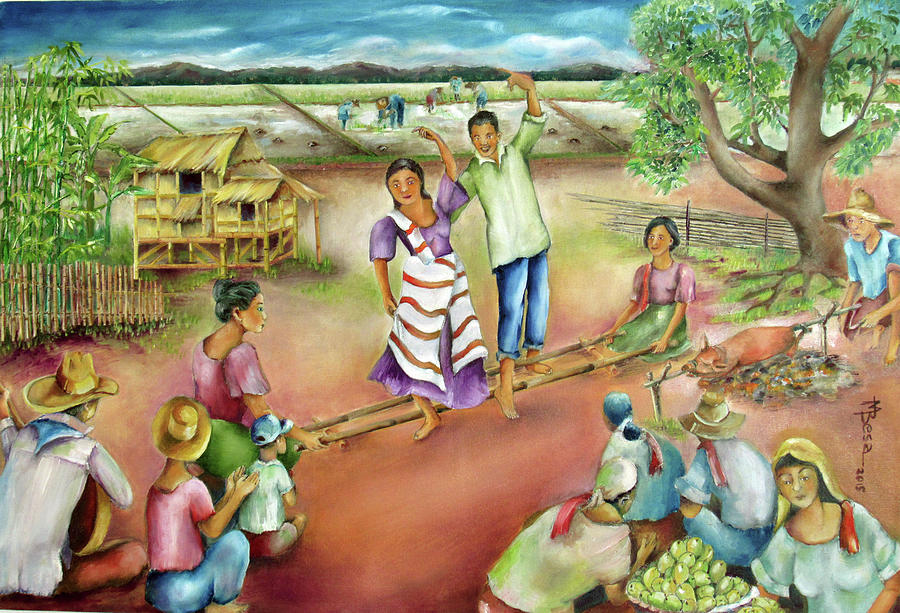

As I’ve said elsewhere, a family will go into hock just to preserve the family honor on the occasion of a fiesta. The scions of a family are willing to devote their young lives in pursuit of a vendetta that spans generations, long after the original offense has ceased to make sense. Individuals refuse financial gain because of the determination to feed their families with the fruits of honest labor.

One could call these examples quaint, I suppose, but that would presuppose that the person who does so lives in a world where honor is unusual enough to be considered charming and old-fashioned. That person should be pitied.

And considered wrong.

He would be wrong also, he who dismisses these acts as easy to do. Hunger, financial disadvantage, death – these are the consequences of these acts of honor. And none of those things exactly fit the definition of “easy.” It is easier, in fact to simply skip the feast. After all, in today’s money-strapped world, who would blame you? But, the thought of the family’s history being dimmed is repeatedly shown to be a powerful motivator.

It would be easier too, to simply remove oneself from the conflicts between families, and yet, young men and women stay behind, desiring to uphold family honor. And nothing could be easier, I suppose, than to skim the top off of donations, if only to get a little breathing room against all the household expenses. But, again, the determination to live up to a moral code proves to be a great motivator.

Far from being unusual or easy, those examples persist to this very day. Acts stemming from the core value of honor are repeated on a daily basis throughout the country, making it a vibrant part of Filipino life and society.

Pressed to provide more examples, we might consider how we view debts of gratitude.

At the root of utang na loob is the deeply held belief that value must be given for value received. This is a responsibility that many Filipinos take on voluntarily. In fact, it is considered poor form to do a favor while explicitly saying that something is expected in return. Do a Filipino a favor and he will hold himself indebted to you, the debt to be repaid either when he is able or when you need it most. It has been fashionable of late to hold this up as a negative trait seeing as how some politicians have taken to using it as leverage. That’s poor form too, but for the Filipino, that hardly matters. Favors need to be repaid. Good for the Filipino who repays the favor, bad for the person who takes advantage of the Filipino that way.

Ever heard of the “pay it forward movement?” Same thing. Only in paying it forward, the anonymity of the giver acts to relieve the person who received the favor of the burden to repay him. But still, the person who receives the favor is asked to do something good for some other stranger, in the same fashion. Utang na loob. It is as Filipino as pointing with your lips, and it is rooted in the concept of honor.

Taken individually, it might be easy to dismiss these common acts as meaningless from a macro point of view. But that’s just laziness and a predisposition to cynicism, coupled with an overweening love for everything other.

But consider this:

The willingness to go into debt to preserve a family tradition during a feast is nearly indistinguishable from the concept of hospitality so central to nearly all cultures and to the, you guessed it, burgeoning field of hospitality. Here in the Philippines, hospitality is a growth industry as we struggle to hedge our beautiful vistas with excellent tourist service. After all, what’s the use of having a brilliant beach if the hotels near the sand are fleabags?

The willingness to lose life and limb for the honor of one’s family is central to the success of the Israelis who view the State as part of their family unit. The same goes for Switzerland where military training for nearly every citizen is not considered militarization but home defense. Defense of the home where they all live as a family.

And isn’t the determination to provide one’s family universal?

There’s an anecdote about an American couple – both in the military – on furlough in Scotland. The wife gives birth in a Scots hospital. As they’re leaving, a Scottish nurse gives them the baby’s feeding card. Since American law prevents servicemen from receiving benefits from foreign countries, the couple refused to accept it. “We’re American,” they said. The nurse snapped back, “Well, I’m really sorry I can’t fix that for you, but the wee lass is a Scot and she gets taken care of by Scotland.”

Family may seem like an antiquated notion to some people, but not to everyone.

None of these three examples are exactly descriptive of life in the Philippines today, admittedly. But they represent the possible directions we can with the core value of honor that is already present in our society. The trick is to extend our sense of family ties outward to include our nation and our tribe.

And in that, we have failed so far.

But not from a lack of honor, but merely because of the crushing influence our history has had on our development as a society.

History matters, and looking back on it to find the causes of what we are now is not whining. It is schooling.

The trouble with many opinionistas today is that it has become fashionable to look at more developed nations and be enamored at the great strides they have made. This, coupled with nice sounding declarative statements of “we have no excuse!” do more damage than good. These exhortations do not resonate with the people because they are rooted in the dismissal of who we are, rather than the sincere desire to understand us and help us find a way around the handicaps we suffer.

Since I’ve said much of what follows before, I’ll just give you the Cliff notes version:

Being under a foreign powers that were intent on maintaining our state of subjugation, under the camouflage of “civilization,” taught us that (a) servility to the authorities is a necessary to get ahead in the world. After all, the masters treat the flunkies much better than they treat the independent minded; (b) a person can benefit his family the most by rising to positions of authority. Once that is achieved, authority must be clung to at all costs, lest the family be allowed to slide back into disadvantage. And to hold on, one must play the game by the rules one used to rise up the ladder in the first place. Perpetuating the power dynamics, therefore, is an essential concept; (c) the ability to circumvent authority is a survival trait. If you can’t get what you need from the authorities that look down on you, you have to be crafty and resourceful. In a word, maabilidad.

Is any of this starting to sound familiar yet? This exact same pattern persists today because we were hardly ever allowed the opportunity to change any of this. The Americans, chaffing under the rule of England declared that their existing form of government – the monarchy – was no longer fit for them, thus they invoked the right to change it.

We did too. We invoked the right to throw of the yoke of colony. But where the Americans got their chance and – under the guidance of those enlightened enough to come to the conclusion of independence in the first place – re-ordered their society as a direct reaction to everything they hated under the old regime.

Standing on the same cusp of history, we were handed over to another overlord. Our moment to blossom as a society, therefore, was taken away from us. And to add insult to injury, we lost our emerging freedom to a nation we had considered a friend. Imagine the shock to the psyche that betrayal must have been.

As a result, learned patterns from the old masters inevitably reasserted themselves under the new regime. Sure, the reins of power changed hands, but the power dynamics remained unchanged. Have we had, since then, the opportunity to recover our lost moment of blossoming?

No, we have not. Instead, we moved smoothly into a Commonwealth phase and into independence. But even then, it was a shadow game played by the brown-skinned who were already in power. Where does that leave us?

Well, we still believe that “(a) servility to the authorities is a necessary to get ahead in the world. After all, the masters treat the flunkies much better than they treat the independent minded; (b) a person can benefit his family the most by rising to positions of authority. Once that is achieved, authority must be clung to at all costs, lest the family be allowed to slide back into disadvantage. And to hold on, one must play the game by the rules one used to rise up the ladder in the first place. Perpetuating the power dynamics, therefore, is an essential concept; (c) the ability to circumvent authority is a survival trait. If you can’t get what you need from the authorities that look down on you, you have to be crafty and resourceful. In a word, maabilidad.”

And can you blame us? Can you reasonably look down on us and sneer “you’re doing it all wrong, Filipinos!” We are doing, as a people, what we have been taught to do, at gunpoint.

Can we break this kind of conditioning? Of course, we can. But just like screaming invective and abuse at a runner from the sidelines isn’t going to make him go any faster, neither can being called stupid or wrong-headed or dishonorable work. Try that with your colleagues or your wife and see where it gets you. LOL

So. History.

- Our history has created in us this dysfunctional view of authority and nationhood. We remain leery of authority and fearful of power. Thus, our laws are paranoid. Most especially after the fall of the dictatorship.

- But when we get power for ourselves, we see the laws as being subservient to the more preeminent need to maintain power. Thus, our laws are more difficult to untangle.

- We are, as a people, also afraid of humiliation (yet another thing learned after generations of de-humanization) and of getting things wrong. Thus, we prefer our laws and regulations to be as specific as possible, to avoid the existence of grey areas where we might get called upon to actually *gasp* decide and then get things humiliatingly wrong.

- We are also subservient and fearful of conflict. Thus the excruciatingly detailed laws are beneficial to us because we don’t need to prove someone did the wrong thing, merely point out that what they did was against the law.

- We see ourselves as virtually living in the interstices of the power structure. Thus, we have raised abilidad to the level of art by which we survive and thrive.From abilidad, it is a short step to corruption – both petty and grand – and one-upsmanship. And yet, for all that, we remain bound by the ties of honor and shame to those we consider as being within our family.

These feel like very primitive patterns, to my mind. But they do not speak of a dishonorable people. Just a people who reserve their debts of honor to those that are closest to them and not to those they feel threatened by. So like I said, the trick is to get people to extend their definition of family to encompass the entire tribe. If we can do that, then honor – which is already a very powerful force in Filipino tradition – can be one of the cornerstones of our success.

So, to go back to the original proposition: That honor is not a strong part of Filipino culture.Bunk. It is part of our culture; but it is not yet the backbone of development and growth that all of us would like to see it become. To confuse that state of affairs with ‘weakness’ or perhaps lack of effect on growth and development, is wrong. The sense and adherence to honor is merely not pointed in that direction yet.The influence of honor, strong as its currents are in our culture, are mostly inwardly directed to those circles we consider ‘family’ (in the general sense of the word, not necessarily genetic or biological). This, however, probably accounts for the perception of some that ‘we are a dishonorable people.’ It would, in fact, perhaps be more accurate to say instead that we are not yet a nation.